Our region is ill-prepared for 'the big one'

By Joe Mahr and Phillip O'Connor

ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH

Saturday, Nov. 19 2005

PIGGOT, ARK.

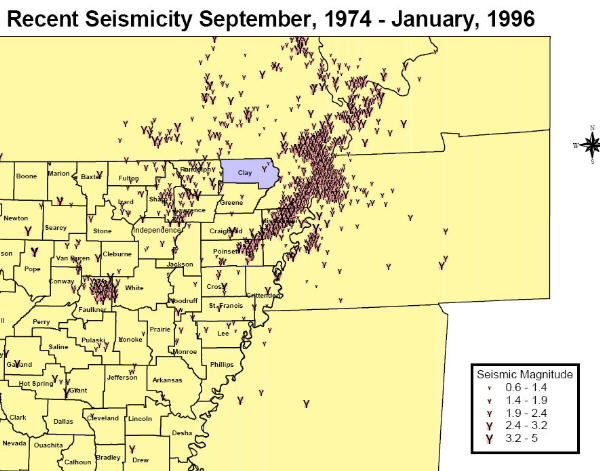

Gary Howell peered around his quaint town and nonchalantly described how it would be decimated when a major earthquake erupted from the nearby New Madrid Fault.

Most of the century-old brick buildings would topple. So would the police station. The emergency operations center for Clay County - housed in the courthouse - would be crushed from chunks of the concrete ceiling.

|

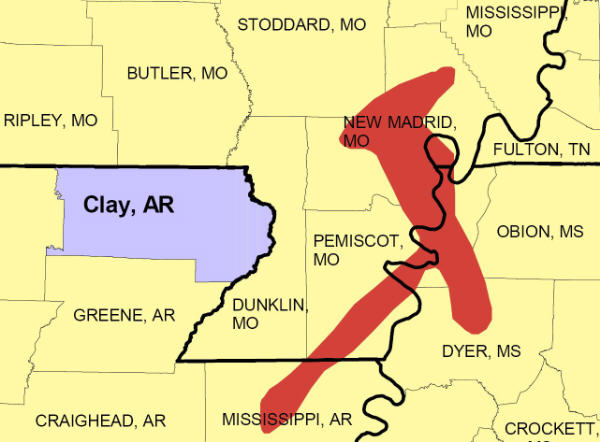

| Clay Co. AR and New Madrid Fault |

|---|

And this is a place touted as a model for earthquake preparedness.

"We're not ready," said Howell, the county's longtime chief executive officer.

More than two decades after federal and state officials called for massive preparations for a major earthquake in this region, including St. Louis, a Post-Dispatch investigation found that government has failed to marshal many of its own resources to prepare for a disaster that could rival the devastation of Hurricane Katrina.

Repeated recommendations from all levels of government in an eight-state region of the central United States have been largely ignored on how to best brace for an event that scientists expect to kill thousands and cause widespread chaos.

"We are entirely unprepared," said Amr Elnashai, who runs the Mid-America Earthquake Center at the University of Illinois. "It is really amazing - really amazing. How can a country as rich and prosperous as the U.S. leave itself in peril this way?"

In a review of thousands of pages of studies and reports and in interviews with more than 150 government officials, researchers and preparedness advocates, the newspaper found:

Many government agencies still haven't estimated the kind of damage their emergency facilities will sustain, which could cripple response efforts in some areas even before the shaking stops.

There's no plan to ensure that older schools renovate to more stringent building codes - or even employ low-cost fixes - to lessen the chances they'll become death traps in a daytime earthquake.

Government agencies don't require utilities to share what types of disruptions and hazardous material spills they expect in an earthquake - nor their plans on fixing problem areas.

Many key bridges remain vulnerable to an earthquake, and some states have no special programs designed to fix these weak links in the transportation infrastructure.

More than 80 percent of counties across the eight-state region are late to file required plans on how best to prepare for an earthquake and other disasters. Until they do, they can't get federal cash for improvements.

Earthquake drills and exercises, regarded by many as key training tools for such an emergency, haven't been held in some communities in more than a decade.

That's not to say there hasn't been progress. Decades of outreach campaigns persuaded some in private industry to strengthen buildings. Government-sponsored research better explained the risks and danger zones. Billions in terrorism grants were spent on new equipment and terrorism training - which will improve response to an earthquake. And some communities received grants to assess or strengthen key facilities. That includes Howell's Clay County, which reinforced two schools and installed a special natural-gas shut-off valve in the courthouse.

But such successes are largely relayed in anecdotes. Citing a lack of cash, time, knowledge and public interest, most government agencies in Missouri, Illinois, Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee have failed to assess what has been accomplished. They've also failed to compile plans on what more they should do to limit casualties and adequately respond to what many planners believe to be the deadliest natural disaster facing the central United States.

Jim Wilkinson, who runs a 22-year-old federally funded agency trying to address the problem, said there was just too little money and public demand to properly prepare a region of 12 million people.

"The list of things that need to be done just goes on and on," said Wilkinson, of the Central United States Earthquake Consortium. "It's almost impossible to put your arms around this situation."

Preparations are hit-and-miss from state to state, town to town and building to building. Many affluent areas with newer building stock also have the full-time planning staffs to snag coveted grant money to plan more and buy more equipment. But poorer, rural communities - including many in what are expected to be the hardest-hit areas - are laden with older buildings and employ only part-time emergency planners with little time or experience to compete for grants for new buildings, renovations or earthquake training.

They're left to play the odds for a catastrophic earthquake. Experts put those odds at a 7 to 10 percent chance in the next 50 years.

Key facilities at risk

Forget trying to get every privately owned home, apartment building and office tower in shape to survive a massive earthquake. Forget trying to force builders across the central United States to follow the latest industry guidelines for seismic design. The government has largely failed to ensure the reliability of even much of its own key infrastructure.

For decades the government's own experts have recommended that federal, state and local officials check their "critical facilities" - structures that will be nerve centers for coordinating rescuers. These include the thousands of older 911 centers, police stations, firehouses, hospitals, schools and other emergency shelters that were built before governments adopted more stringent building codes in the 1990s.

Buildings such as the Jefferson County courthouse.

Dating back to the Civil War, the brick building sits amid the rolling hills of Missouri's fifth-most-populated county. The county added wings in 1895 and 1957 - long before building codes addressed earthquakes. The last addition is reinforced, but officials aren't sure about anything built earlier. And unreinforced stone or brick buildings are least resistant to rolling and twisting seismic waves.

"I would doubt very seriously it would stand up to a major earthquake," said Brian Counsell.

That's a problem for Counsell, who's responsible for coordinating disaster response for the fast-growing county. The emergency operations center - stocked with phones, TVs, radios and computers - sits in the courthouse basement.

But, he said, there is no money for expensive retrofits, improvements designed to make buildings better withstand earthquakes. In a state struggling to prepare for more common disasters such as floods and tornadoes, there's no money set aside to even evaluate major buildings for their earthquake vulnerability - despite repeated recommendations suggesting it be done.

As far back as 1989, the Federal Emergency Management Agency recommended that all levels of government assess their critical facilities. In 1997, a legislatively established expert panel, the Missouri Seismic Safety Commission, recommended the same. So did a special study for Jefferson County and much of metro St. Louis, completed by the East-West Gateway Council of Governments and approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency just last year.

But nobody's checking.

"I can't tell you what's been done or what hasn't been done," said Martha Kopper, who wrote the council's report. "It's up to them (local officials) to follow up."

Most states and counties haven't pushed such evaluations. One exception is Illinois, which in the mid-1990s oversaw a basic assessment of all the Southern Illinois buildings it deemed critical, including churches and fraternal lodges. Another exception is St. Louis County, which studied 1,200 facilities a decade ago. But nobody has followed up to see if vulnerable buildings were updated. The county didn't even keep its list.

Missouri's seismic safety commission wanted somebody to keep track. In its 1997 report to the governor and Legislature, it recommended that each critical facility file a "report of vulnerability" to the state.

The idea was ignored.

Eight years later, longtime commission member Ted Pruess said he was going to recommend - again - that somebody keep track.

"We're not talking big-time money," he said. "We're talking about somebody to track down some reporting issues and to get this thing organized, so we can get the information to see exactly where this state is as a whole, because I don't think anybody knows."

The federal government knows what needs to be done to most of its vulnerable facilities - Congress demanded in 1990 that the issue be addressed. But federal agencies ran out of money to fix most of the problems. That includes the 14-story federal building in the heart of Memphis, the nearest large city at risk from a New Madrid quake.

That means 650 people work in a building that could experience "catastrophic structural failure" in an earthquake - with ceilings and interior walls collapsing, and 6,000-pound exterior panels plunging onto a plaza, according to a 1992 congressional report. The building was supposed to be renovated by 1994. Engineers studied how to do it in 1999. The government still hasn't set aside the cash.

Federal money has been available to allow state and local governments to prepare for earthquakes. But the amount of money has been stagnant for a decade.

Even then, the vast majority of communities never applied for special grants to assess or fix their facilities, and missed deadlines leave many temporarily disqualified from applying for the help.

FEMA told local officials in 2000 to complete a thorough report, by last year, on how to lessen the effects of disasters. But state and local officials complained that anti-terrorism efforts already had them overworked. And, as of the last count taken in August of this year, more than 80 percent of the region's 748 counties had not finished the plans. Missouri is a national leader, even though two-thirds of its counties were late to file.

And the plans are just a start toward preparedness. At best, they contain broad computer modeling of what damage might occur, with no details on which facilities are vulnerable. With a vacuum of knowledge, many emergency planners across the eight-state region rely on anecdotes and assumptions about who's done what and how buildings will fare.

There are the stories of communities that landed rare federal earthquake grants - such as Cape Girardeau, Carbondale and Clay County - and the facilities there that have been upgraded. There's the belief that many hospitals have either renovated or built their way out of bad seismic designs, and that some schools have too - or at least did the much less expensive "non-structural" fixes, such as bolting down bookcases, tying down overhead lights and installing shatter-resistant film on windows.

|

Checks by the Post-Dispatch of scores of critical facilities across eastern Missouri found mixed results. Many hospitals have replaced older structures, or at least part of them. Some schools have rebuilt or at least done non-structural updates. Same with police and fire stations.

But in many of the small towns that dot the Bootheel, the area expected to be the most affected, officials are resigned that many of their critical facilities, even some emergency operations centers, will instantly be rendered useless.

There's little doubt among emergency planners that many critical buildings are not up to the task.

"We've got thousands and thousands of children in schools that are questionable," Wilkinson said.

That's clear in Kennett.

The district asked an engineer in 1990 whether it should retrofit the then-55-year-old brick middle school, and he recommended that it wasn't practical. So they haven't.

His advice ran counter to the lessons children are taught about what to do in an earthquake. Experts tell them to huddle under the desk. His recommendation: immediate evacuation.

Low priorities - bridges at risk

The same year Kennett decided it was impractical to retrofit a school, a Missouri task force decided it was important to retrofit key bridges. Within 10 years, the task force wanted to strengthen 577 bridges across the eastern part of the state that would be critical rescue and evacuation routes.

Another expert panel - the seismic safety commission - made the same recommendation in 1997.

Eight years later, the Missouri Department of Transportation still has no program to retrofit key bridges. Like many other states, Missouri retrofits only spans scheduled for major overhauls.

Dave Snider, a retired state engineer who shaped much of department's earthquake planning, said the state already struggled to fix dangerous and congested roadways.

"It (retrofitting) became a lower priority because we're not California. It's that simple."

Missouri has done several high-profile retrofit projects - such as the Poplar Street Bridge and the double-deck portions of U.S. 40 (Interstate 64) - but those are exceptions. The hundreds of bridges on key routes that remain vulnerable won't be touched until the bridges have to be fixed for other reasons. The state doesn't keep a list of bridges needing retrofits. It didn't even keep the task force list of 577 bridges from 1990.

Compare that with Mississippi and Tennessee, which have special programs. Mississippi has done 20 bridges under the program. Tennessee has done 220.

"We've gone through a reawakening on the bridge situation," said Cecil Whaley, of Tennessee's emergency management agency.

Missouri has a different plan: Pick a few routes with the fewest bridges to use to access parts of eastern Missouri. That's why Manchester Road is a top priority route into metro St. Louis, ahead of any interstate.

But problems could be more severe in the Bootheel, where the transportation department's own projections expect 25 percent of bridges to collapse and two-thirds to be seriously damaged in a magnitude 7.6 earthquake - the standard planning guideline. That's as powerful as the quake that devastated northern Pakistan in October.

U.S. 60 - considered the main east-west route into the area - has many bridges that remain vulnerable, some of which can't easily be bypassed.

It's difficult to even catalog what bridges are vulnerable.

Illinois reports more than 500, but there are no figures for Arkansas or Kentucky. Missouri reported 1,400 bridges to a special central U.S. earthquake task force, but now says the data were flawed. A MODOT power-point presentation puts the number at 97.

The latest task force, established in 2000, persuaded the states to connect many of their emergency routes to their neighbors', so evacuees and rescue workers could cross state lines without getting stuck. But the task force has struggled to get federal funding for more studies, and its members can barely find the time and travel money to meet.

"We've got a lot of things on the plate that are lofty goals and things we ought to be doing," said task force chairman Jerry Thompson, of the Indiana Department of Transportation. "We're just not making the progress we'd like."

"Lifelines" could kill

Power lines fall. Natural gas lines rupture. The combination ignites fires. There's little water to extinguish them.

The catastrophic effects of the breakdown of so-called "lifelines" were predicted in a 1990 study by FEMA showing just how chaos would unfold once the shaking stops.

Water and sewer plants in St. Louis could be knocked off-line. Leaks and ruptures would spring along thousands of miles of piping. And even if the water and sewer systems still worked, widespread power outages would make it difficult to run the plants and pump water.

Such scenes could be repeated across much of the eight-state region. Not only do southeastern Missouri and northeastern Arkansas sit on the predicted epicenter and have the type of soil that can turn into quicksand, they also house major pipelines that ferry fuel from the Gulf Coast to the East Coast - producing more risk for hazardous leaks.

Just as the government's own experts have recommended that authorities assess and shore up their critical structures, the same pleas have been made for decades for utility infrastructure.

Those pleas have been met with largely the same results.

Newer lines have been built to better standards. Utilities' emergency plans have been updated. Other improvements are known anecdotally.

In Cape Girardeau, a shut-off valve on the water tower will keep the water from gushing out in a line break. Laclede Gas has replaced some cast iron piping with more flexible plastic. AmerenUE has bolted down substation transformers.

Still, there's been no comprehensive assessment of utility vulnerabilities, or a plan to fix them. Utilities are not required to study or report such vulnerabilities to the state and federal agencies responsible for safeguarding the public.

In Kentucky, Steve Oglesby, with that state's emergency management agency, can't even find out where pipelines are situated.

"I've worked through our state public service commission," he said. "They came back and told me it's hard to get information from the companies where the pipelines are located because of homeland security issues."

Stoddard County pipelines

Bill Pippens knows exactly where the pipelines are in his county - one that runs mostly liquefied gas, the other jet fuel, diesel, gasoline and other refined petroleum from Texas to the East Coast. The World War II-era, carbon steel pipes run 3 to 5 feet deep under the eastern edge of Dexter, Mo., surfacing every few miles, including at a storage facility just on the edge of town where hundreds of thousands of gallons of propane is stored in large tanks.

What the Stoddard County emergency management director doesn't know is how much could spill in an earthquake and how it would get cleaned up.

"We're afraid that when things start rumbling and shaking, you're going to have those tanks fall off their pedestals, and then you're going to have eruptions from the earthquakes on the pipelines themselves," he said.

He knows the utility company has trained response crews and plans to shut off valves every 7 to 20 miles, but he's unsure how long it would take them to shut down the flow if the electronics shut down. He remembers it took the company 45 minutes to turn off a leak of jet fuel that spewed from the pipeline in a 70-foot geyser. He said they were lucky that day. The wind carried the fuel mist away from the flames of two large corn dryers.

"One spark and we would have been sitting on a crater the size of Busch Stadium," he said.

Rescue training spotty

Thirty miles through the cotton fields and flat delta, Ronnie Adams laughs at just how unprepared New Madrid County is.

His county was the site of the largest earthquake ever to hit the continental United States, in 1812, and the next catastrophic earthquake is expected to kill one in 10 county residents, according to a Missouri study. One of every seven survivors will be seriously injured.

Adams gets $4,000 a year to coordinate the county's disaster response. That's not enough to conduct drills.

"When you start doing that, you've got to buy gas and buy this," Adams said.

The gulf in preparations for the next major earthquake extends to those who'd be called upon to rescue and aid the trapped and dying.

Flush with federal grants to prepare for terrorists, bigger departments bought new equipment, beefed up response plans, strengthened mutual aid pacts and drilled to hone their skills. The state National Guard has special mobile communication gear that can help coordinate rescuers' radio communications. But hurdles remain.

On Friday, Missouri Public Safety Director Mark James acknowledged that state and local plans geared to generically handle any kind of hazard remain inadequate for a massive earthquake. That realization prompted state officials to begin writing a new plan to fix expected problem areas, such as clogged or impassable evacuation routes, overburdened shelters and overworked morgues trying to collect and process thousands of dead.

"There's a big difference in the required response to a tornado that comes through and damages a significant portion of a town to (the response for) an 8.0 on the Richter scale that can run all the way from Memphis to halfway to Chicago, and in its path impact small communities and the city of St. Louis," James said. Most deaths are expected to occur outside urban areas such as St. Louis. In addition to New Madrid County's 1,800 dead, federal computer models predict another 1,800 deaths in Mississippi County. And 1,200 in Pemiscot County.

But the limited federal grant money that has reached those towns is still focused on preparing for terrorists. That's why Portageville police now have gas masks and work boots for a chemical or biological attack.

"That's just going to sit back there and rot," Adams said.

Much of Southern Illinois, northeastern Arkansas and western Kentucky have not started special citizen-volunteer teams to help beleaguered rescue workers in a catastrophe. Most states haven't followed Missouri's model of enlisting volunteer engineers to assess the safety of buildings after earthquakes - key to quickly opening shelters and other critical facilities.

There hasn't been a comprehensive New Madrid earthquake drill with all levels of government since the early 1990s, although one is being planned for 2007.

FEMA deemed the training so important that it gave higher priority to only one other catastrophe it feared could occur. That exercise was held last year.

It involved a major hurricane hitting New Orleans.

joe.mahr@post-dispatch.com 314-340-8101

poconnor@post-dispatch.com 314-340-8321

Powered by ShowMe-Net